It’s a familiar story: a venture capital firm invests in a small technology startup that goes on to see huge growth and an eventual sale to a large tech company like Facebook or a successful IPO, giving the venture capital firm a massive return on its initial investment.

Although that may sound like a scenario exclusive to dot-com booms and startups in the 21st Century, it’s also the story of American Research and Development Corp. and its 1957 investment in Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC), which arose in the Boston area, not Silicon Valley. Led by Georges Doriot, often called ”the father of venture capital,” ARDC’s $70,000 investment in DEC grew to $355 million — 500 times ARDC’s initial investment — when DEC held its initial public offering in 1968. (For a great biography of Georges Doriot, please read Creative Capital: Georges Doriot and the Birth of Venture Capital, by Spencer E. Ante.)

Although they’ve been around a while, the lore of venture capitalists (or VCs) is most strongly tied to the startup culture that first emerged from Silicon Valley in the late 1990s and continues to this day. You may have heard heady tales of fantastic riches (and disastrous dot-com busts), but what role does a venture capitalist actually play in the life of a startup?

What a Venture Capitalist Is

Silicon Valley mythology and history lessons aside, the role of venture capitalists in the startup ecosystem can’t be understated; without VCs, there’d be no startup economy. In general, a venture capitalist is an investor who provides capital to a company in exchange for an equity stake (shares in the company). More specifically:

A venture capitalist is an investor willing to take on high risk for high return: Risk is at the core of venture capital. Venture capitalists are willing to invest in companies that are, statistically, very likely to fail – in fact, the failure rate of venture-backed companies in recent years has been reported at about 75 percent.

Why make an investment that has a 3 in 4 chance of coming up a big zero? Because the other 1 in 4 just might bring astronomical returns. Although 8 percent annual growth is solid for your 401(k) and your real-estate agent will tell you a 50 percent return over a few years is a pretty sweet deal, a venture capitalist is looking for returns above 500 percent. Startup founders are not going to win over any VCs by telling them their startup would double their investment — venture capitalists love and more importantly need 10x returns, not 2x.

It’s that sort of return that can cover investments in many failures and still leave a handsome pile of cash at the end of the day for the venture capitalist’s investors in her or his fund. ”We all work for someone,” successful VCs like to say, and venture capitalists work for their investors or limited partners to get them their money back and 4xs on the original investment. To do that, venture capitalists make a lot of bets and hope that more than 20 percent will pay back 10+ times to cover the other 70% to 80% that won’t return capital, let alone a return on capital.

A venture capitalist is an owner: In exchange for their cash investment, a venture capitalist purchases equity in a startup in the form of preferred stock. And as with any other stockholder of any company, that makes the venture capitalist an owner, but one with preferences and protections, in particular preferred voting rights.

This brings up two critical points for startup founders to understand: a venture capital investment both dilutes founders’ ownership of their company and causes the founders to hand over some control of the company to the VC. It’s not uncommon to see cash-hungry startup founders give up too much control and equity to their venture capital investors, and when it comes time to exit, the VCs can be a bit happier with the ledger than the founders.

A venture capitalist is involved with the companies it invests in: When a venture capital firm invests in a startup, the investor’s role should be more than just that of a large shareholder. Value-added investors and venture capitalists serve in an informal and sometimes formal advisory role, especially when their years of experience working in and with startups can help guide founders who are launching their first venture. More formally, as part of the investment terms, a venture capitalist is often granted a seat on a startup’s board of directors.

Most venture capitalists specialize in one sector, building experience while working with many companies in a specific industry such as fintech, insurance tech or consumer products; this focus helps VCs identify the next big breakout startups. In turn, venture capitalists make this expertise available to the firms they advise.

Venture capital firms also may help cash-strapped startups with key services such as marketing, human resources, or office space. Andreesen Horowitz prides itself on the power of its platform in helping startups accelerate faster with a16z, as opposed to competitor investors.

What a Venture Capitalist Is Not

The term ”investor” is sometimes used to mean ”venture capitalist,” but it’s really too loose a term. For example:

A venture capitalist isn’t a bank: Founders don’t apply for a loan with a VC and pay it back later with a little bit of interest on top. Venture capital investment involves getting a stake in a company and influencing its future (and a lot more than just a little interest on top).

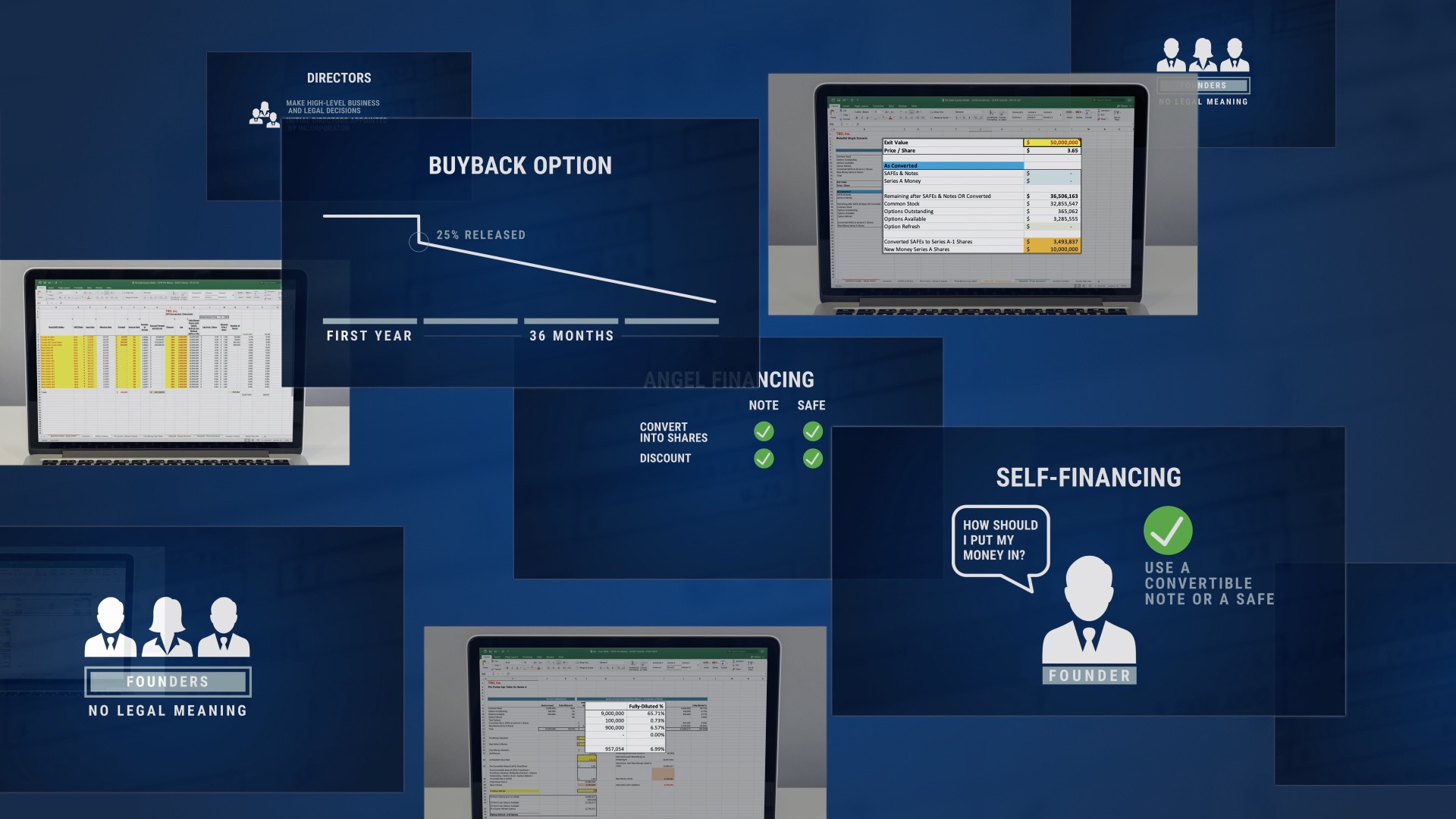

A venture capitalist is not usually the first investor in a startup: Venture capitalists target startups that are ready for ”commercialization,” a stage in a startup’s life where it’s ready to launch or scale a product widely and (hopefully) begin exponential growth. Investment before commercialization usually comes from the founders themselves and angels — friends, family and other smaller investors.

A venture capitalist is not a charitable benefactor: VCs are investing, not donating, and will seek terms that benefit themselves. Although founders and venture capitalists have the same goal – building a successful company that has a great exit – founders should be prepared to negotiate with venture capitalists, ensuring that the handing over of some stake in the company and ceding some control is worth the investment.

Making your Startup Ready for Venture Capitalists

If you’re launching a startup that wants to one day win venture capital investments, you’ll need to form your company in a certain way and truly understand your equity position before you think about pursuing VC funding. StartupProgram.com’s Venture Academy can teach you how to form a venture-ready company and understand your ownership stake in your firm, both before and after a potential venture capital investment. The knowledge you’ll gain from this online lecture series gives you confidence when the time comes to pitch venture capitalists.

StartupProgram.com’s Professional Services adds consultation from our partner law firm, O&A, P.C., as well as automated document creation and filing, helping you get your company formed quickly – and well-prepared for VCs.